Hydration: why water matters — and how to stay hydrated even in winter

Water is the unsung hero of nutrition and health. As roughly 60–70% of our adult bodies are water, it plays a fundamental role in nearly every physiological process: transporting nutrients, flushing out waste, regulating body temperature, supporting cardiovascular function, and maintaining healthy tissues and organs.

It is government recommendation in the Eatwell Guide to have six to eight glasses of fluid per day. Despite its critical importance, water often becomes a neglected nutrient. During the colder months from November to February, we often don’t feel as thirsty and tend to drink less. This can lead to dehydration, which is just as dangerous in winter as it is in summer—affecting cognition, mood, digestion, and overall health.

The science behind hydration & brain health

Hydration is consistently shown in research to enhance cognitive function. Controlled trials, suggests that hydration status affects mood, cognition and mental performance. For example, in a self‑controlled trial involving 12 healthy young men between the ages of 18 – 25 years, those who experienced mild dehydration exhibited worse performance on tests of attention, memory and mood — impairments that improved after rehydration. (Zhang et al., 2019).

The effects of dehydration and the level of dehydration vary based on individual factors such as age, physical activity output and general health status. A recent large prospective study followed nearly 2,000 older adults (aged 55–75) who were overweight/obese (BMI ≥ 27 kg/m² and < 40 kg/m²) over a two-year period. It found that participants with lower hydration status, as indicated by higher serum osmolarity (measure of dissolved substances in the blood), had greater decline in global cognitive function over the follow‑up period compared to those who remained hydrated. (Nishi et al., 2023).

A growing body of evidence underscores that adequate fluid intake isn’t just about preventing thirst or dehydration sickness; it’s intimately linked to cognitive health, mood stability, and long-term brain function which is vital for productivity, well‑being and healthy ageing.

Hydration needs across the life course

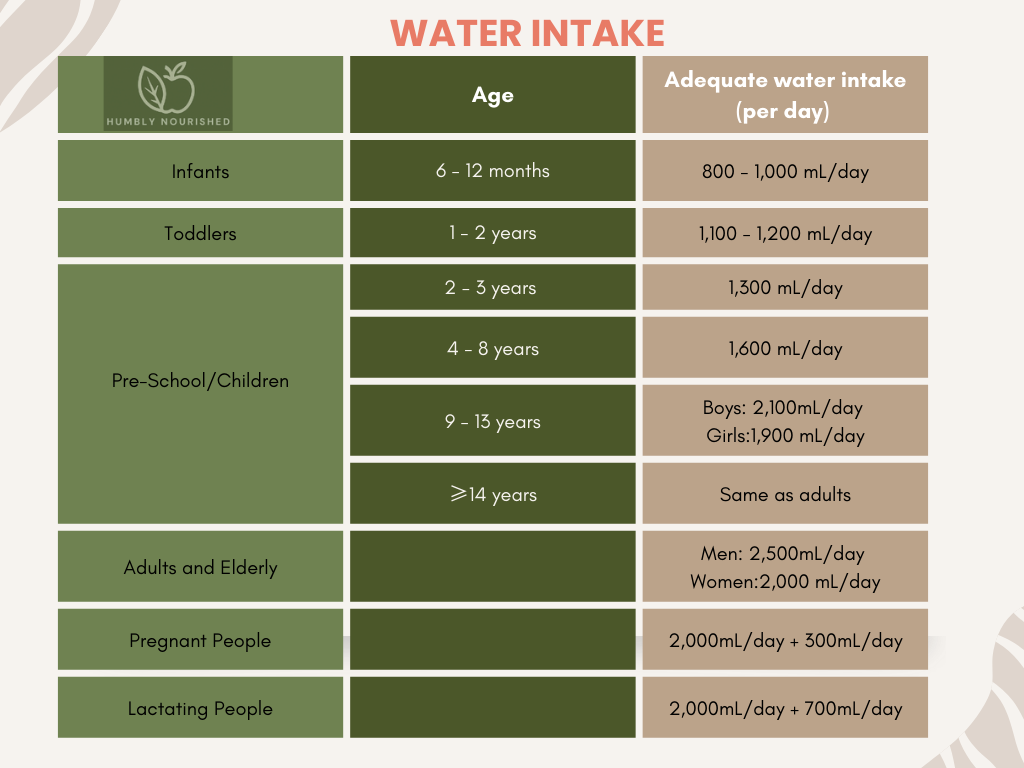

Hydration requirements differ markedly by age. Infants and young children have a much higher proportion of body water which is typically 70–80% of body weight. They can also lose fluids more rapidly than adults, making them particularly vulnerable to dehydration. Their kidneys are also less able to concentrate urine efficiently, meaning water losses can accumulate quickly. By adolescence, total body water stabilises, but patterns of under-hydration often develop as many young people replace plain water with sweetened drinks.

As summarised by Chouraqui (2022, Nutrition Reviews 81:610–624), “children are not little adults” when it comes to water needs: their higher metabolic rate, larger skin-surface-to-mass ratio, and physiological immaturity mean they require more fluids per kilogram of body weight than adults. Recognising these age-related differences helps tailor advice and helps promote regular hydration habits from childhood through to adulthood. Below is a helpful table on water intake recommendations from the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA).

Winter hydration: why you might inadvertently dehydrate

In winter, environmental factors conspire to make dehydration more likely: cold air outdoors and central heating indoors both dry out the air, accelerating water loss through skin and breath. Additionally, cold tends to blunt our thirst response by up to 40%, meaning we simply feel less like drinking (Kenefick et al., 2004). As a result, we may lose fluids without realising.

Practical tips for staying well‑hydrated in winter

Here are 5 practical ways to maintain hydration even when you don’t “feel like” drinking:

- Sip warm drinks — Opt for warm (not scalding) water, herbal teas, or decaffeinated infusions. Warm fluids are more comforting in cold weather and may encourage you to drink more often. Keep insulated bottles or mugs on hand to keep your liquid warm.

- Set reminders — Use simple prompts (alarms, phone, sticky notes) to remind yourself to take a few sips at regular intervals (e.g. every 30–60 minutes). Accepting that dryness and thirst are less obvious in winter.

- Pair drinking with routine tasks — For example, drink a glass of water after using the bathroom, before making a meal, or before each cup of tea or coffee.

- Choose hydrating foods — Soups, broths, stews, water‑rich vegetables (cucumber, celery, peppers), and fruits (e.g. oranges, kiwi) contribute to overall fluid intake, all of which counts.

- Keep fluids visible and accessible — Place a water jug or a mug on your desk or kitchen counter. Out of sight, out of mind often means out of sip range.

Conclusion

From a nutritionist’s vantage point, hydration is not a “nice to have” but a foundational pillar of health. Influencing everything from digestion, immune function, and skin health to cognitive performance and mood. Even in winter, when thirst wanes, our need for fluids remains just as real.

Check our recipes page for some water-rich soups to try at home – always nutritious and always humble.

References

- Chouraqui, J-P. (2022) ‘Children’s water intake and hydration: a public health issue’,Nutrition Reviews, 81 (5), pp. 610–624. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuac073

- Kenefick, R.W., Hazzard, M.P., Mahood, N.V. and Castellani, J.W. (2004) ‘Thirst sensations and AVP responses at rest and during exercise-cold exposure’,Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 36 (9), pp. 1528–1534. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000139901.63911.75

- Nishi, S.K., Babio, N., Martínez-González, M.A.et al. (2023) ‘Hydration status and 2-year changes in cognitive performance in older adults: the PREDIMED-Plus study’, BMC Medicine, 21 (1), p. 85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-02771-4

- Public Health England (2016)The Eatwell Guide. London: Crown Copyright. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-eatwell-guide (Accessed 30 November 2025).

- Zhang, N., Du, S., Zhang, J., Ma, G. and Zhang, J. (2019) ‘Effects of dehydration and rehydration on cognitive performance and mood among young men’,Nutrients, 11 (6), p. 1371. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11061371

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition, and Allergies (NDA). (2010) Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for Water. EFSA Journal, 8(3): 1459.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this blog is for general informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional healthcare or medical advice. Always consult with a qualified healthcare provider to discuss your individual needs before making any changes to your diet or lifestyle.

Leave a comment